Nova Scotia castaways

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

NRP Afonso de Albuquerque

(Portugal)

Captain: José de Brito (Cap. de Mar e Guerra)

Type: Sloop

Tonnage: 2440 GT

Owner: Portuguese Navy

Port: Lisbon

Built: Hawthorn Leslie and Company (1935)

At thirteen hours and twelve minutes on November 29, 1942, the crew of the Portuguese Navy sloop Afonso de Albuquerque saw the first signs of the sinking when a floating mattress passed by. Thirteen minutes later they detected the first rafts with survivors and 27 hours later they concluded the largest rescue operation carried out by Portuguese ships in any of the oceans, saving a total of 194 people.

All of them belonged to the British liner Nova Scotia, transformed into a troop transport, sunk, on the morning of the 28th, by the German submarine U-177, which fired three accurate torpedoes shortly after seven morning. In less than ten minutes, it sank, leaving 1,052 people shipwrecked, 766 of which were Italian prisoners and internees, among whom were three women, one with an 11-year-old daughter. The rest were English and South African soldiers or prison guards.

The ship had come down from the Suez area, passed through the Mozambique chanel before being attacked near the coast of Natal. Of those on board, many lost their lives immediately and others in the following hours and days. The eleven-year-old child drown shortly after the attack when the vest she was wearing came loose as she fell into the water.

When the U-boat commander, Robert Gysae, surfaced to interrogate the castaways he realized that the majority were Italian civilians. As the attack took place after the Laconia case - when U-boats on a rescue mission were attacked by Allied planes - the order not to carry out rescues was already in force. So the German officer radioed Berlin, which informed the Reich Legation in Lisbon and they, finally, contacted the Portuguese authorities.

Nova Scotia

(GB)

Capitain: Alfred Hender

Type: Troop Transport

Tonnage: 6,796 GT

Owner: Furness, Withy & Co Ltd

Port: Liverpool

Built: Vickers Ltd, Barrow-in-Furness (1926)

A group of Nova Scotia castaways on the wreckage of the ship

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

NRP Afonso de Albuquerque rescueboat picking castaways

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

It was only in the early evening of the 28th - 14 hours after the attack - that the message completed its journey to Lourenço Marques, where the sloop Afonso de Albuquerque and Gonçalves Zarco were stationed, in final preparations to return to Lisbon. The first got ready and set sail at dawn. Gonçalves Zarco's commander also wanted to follow, but was ordered not to. He would only be called if necessary.

It was half past two in the morning when the ship headed south and at noon, after sailing 160 miles, they reached the coordinates advanced by the submarine, but found nothing. Only an hour later, further south, did they find evidence of the disaster that had hit Nova Scotia. The wreckage was scattered. There were isolated rafts and at least one rescueboat with a blue flag with survivors. There were also people clinging to all kinds of floating debris.

The commander decided to leave the lifeboat - which seemed in a safer situation - until last and began to pick those who were on rafts, wreckage or otherwise scattered, trying to prevent them from floating further away. To make the work easier, they lowered lifeboats and a longboat with a engine. At 4 pm they found one of the women. At about the same time, on the sloop, a British officer died, despite the doctor's efforts. By nightfall they had found 122 people and the operation continued using lights.

When the sun rose, they found themselves at the center of the tragedy, with hundreds of bodies floating around Afonso de Albuquerque.

Castaway being hoisted onto the Portuguese ship

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

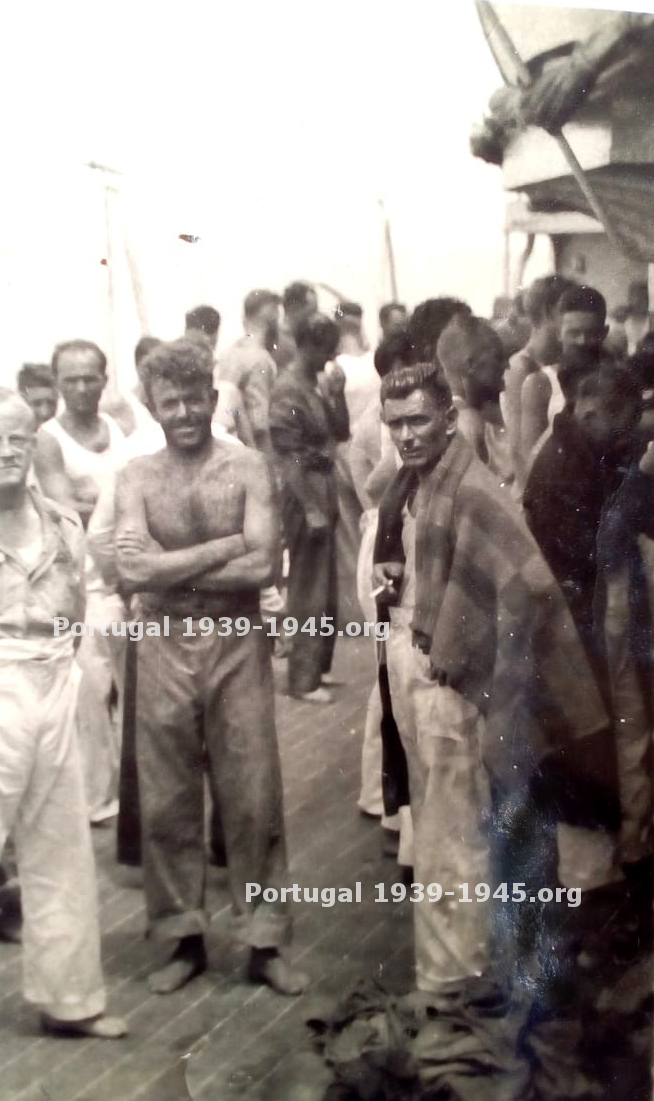

Shipwrecked aboard the Afonso de Albuquerque

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

More castaways aboard the Afonso de Albuquerque

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

In a booklet, published by the Military Naval Club in 1952, 1st lieutenant Gomes Ramos, remembered the resilience of those who were saved with the example of the woman who lost her daughter and swam alone for 30 hours until she found a place on a raft. A vacancy left by a man who, in desperation, decided to die by jumping into the water.

Two days after the sinking, the Portuguese found an exhausted man, sleeping soundly, clinging to a gaming table. Among the survivors was a Portuguese descendant who took time to talk about the Gil Eanes ship. Even sadder was the case of a woman who was on a raft and threw herself into the water, trying to swim to the Portuguese ship and was never seen again.

A situation would always be remembered among the Portuguese because it was one of the few acts of humanity between “enemies”. An elderly Italian man repeatedly wanted to throw himself into the sea to reach the Afonso de Albuquerque, but his raft companion, a young British man, always stopped him and, given his accumulated fatigue, certainly saved his life. They were among the last to be found…

Afonso de Albuquerque's crew that rescued the Nova Scotia shipwrecks

(Photos ceded by Mário Pereira)

It was one of the few cases in which they found allies and Italians together.

In most cases they had not mixed, with the fight for a place obeying two criteria: First the law of the strongest and then that of the flag. By punching or stabbing, both groups had gained rights over the floating wreckage. On raft, rubble or rescueboat dominated by Italians, there were no allies and vice versa.

The rivalry continued on the Portuguese ship where hatred and enmity continued to brew. It was necessary to divide the space to avoid problems until arriving in Lourenço Marques, on December 1st.

In the sinking of the Nova Scotia, 212 allied soldiers or civilians and 646 Italian prisoners and internees were lost, but thanks to Portuguese intervention it was possible to save 64 allies and 130 Italians.

Of the latter, unable to get a ship to take them to Italy - as it needed allied authorization - several would stay in Lourenço Marques cooperating with an Axis spy network that operated there.

Carlos Guerreiro

Note: We thank Mário Pereira for providing the photographs. They belonged to the album of his father, Diamantino Pereira, a stoker aboard the NRP Afonso de Albuquerque during the Nova Scotia rescue operation.

Fontes:

National Archives UK, Kew (GB) § Arquivo Histórico da Marinha (PT) § Arquivo Histórico do MNE (PT) § uboat.net § Shipping Company Losses of the second World War, Ian M. Malcolm § Liverpool Maritime Museum/Archive § Lawrence Paterson, Hitlers Grey Wolfes - U-boats in the Indian Ocean §